What Are Hallucinations?

- Published7 Feb 2018

- Reviewed7 Feb 2018

- Author Melissa Galinato

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Hallucinations happen when people see, hear, feel, or otherwise sense things that are not real, but appear to be very real and part of the surrounding environment. Hallucinations usually appear suddenly and cannot be controlled.

Many different things can cause the brain to make images, sounds, and other phenomena appear out of nowhere. Sleep loss, grief, and sensory deprivation can trigger hallucinations in otherwise healthy people. Using substances like psilocybin, LSD, alcohol, stimulants, opioids, and cannabis can spark hallucinations as well. And, diseases and disorders such as brain tumors, dementia, and mood disorders can too.

What areas of the brain are active during a hallucination?

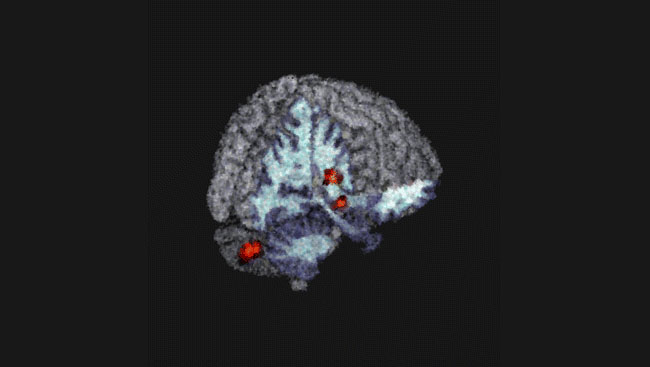

Scientists have used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure brain activity during hallucinations, revealing which regions are involved. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the brain areas responsible for your five main senses are directly affected during hallucinations.

For example, the primary visual cortex is active during hallucinations of colored shapes, because brain cells there are involved in seeing lines and edges. There are also other brain cells that recognize cartoons, famous people, and buildings that are activated both in real life and during visions of those subjects. Hallucinations in the form of voices involve several brain regions important for language, memory, and emotion, including the amygdala and the hippocampus. Understanding how these hallucinations manifest in the brain helps doctors and researchers develop treatments to reduce them.

Do hallucinations only happen to humans?

Adam Halberstadt, a professor who researches hallucinogenic drugs at UC San Diego, says, “LSD causes monkeys to act like they are experiencing visual hallucinations (e.g., they try to grasp nonexistent objects).” Halberstadt also points to other studies using pigeons treated with LSD that suggested the birds were pecking at visual hallucinations. “But unfortunately in those situations it is not possible to know what the animals are actually experiencing.”

This is an important question because animal testing is necessary to research treatments for unwanted hallucinations. Lab mice are an especially helpful tool in this effort.

When mice receive a dose of hallucinogens, they perform what’s known as the ‘head twitch response.’ “Visually, it looks quite similar to the way a dog shakes to dry itself after a bath, but is isolated to the head rather than the full body,” says Landon Klein, a researcher from the Halberstadt Laboratory. The hallucinogens interact with brain cell receptors that are present in both mice and humans, which causes the head movement in mice and hallucinogenic effects in humans. Scientists use the head twitch response to gauge the effectiveness of drugs aimed at blocking hallucinations.

The results of these trials will give us clues about what is happening in the brains of humans as well as mice.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Sacks O. TEDTalks: Oliver Sacks, What Hallucination Reveals about Our Minds. New York, N.Y.: Films Media Group. 2012.

Hoffman RE, Hampson M, Wu K, Anderson AW, Gore JC, et al. Probing the pathophysiology of auditory/verbal hallucinations by combining functional magnetic resonance imaging and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Cerebral Cortex. 17(11), 2733-2743 (2007).

Also In Thinking & Awareness

Trending

Popular articles on BrainFacts.org