Addiction and Brain Circuits

- Published15 Apr 2011

- Reviewed15 Feb 2012

- Author Sarah Bates, MS, MA

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Humans have always struggled with addictions to mind-altering substances. Yet, only in the past few decades have neuroscientists begun to understand precisely how these substances affect the brain — and why they can quickly become a destructive and even deadly habit.

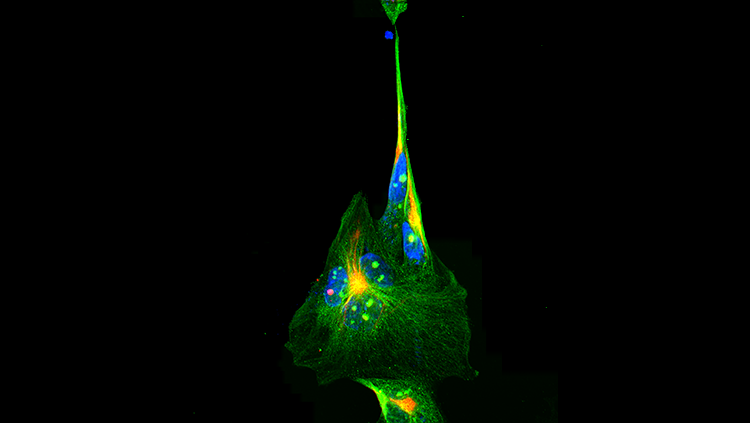

The neurotransmitter dopamine acts on specific receptors in the brain to increase pleasure and reward. The image shows that dopamine produced in one nerve cell activates receptors in neighboring brain cells.

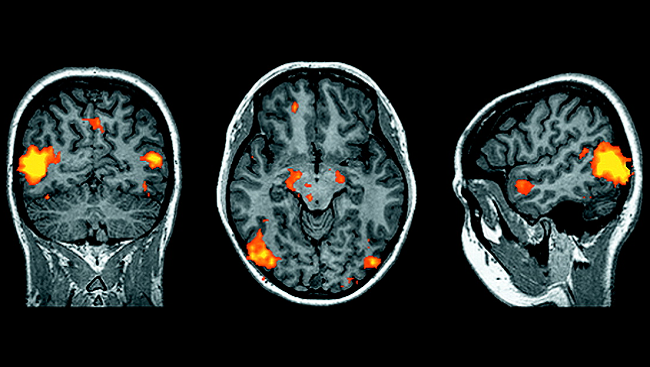

For a long time, society viewed addiction as a moral failing. The addict was seen as someone who simply lacked self-control. Today, thanks to new advances in brain imaging and other technologies, we know that addiction is a disease characterized by profound disruptions in particular routes — or circuits — in the brain.

Scientists are learning how genetics and environmental factors, such as stress, contribute to these neural disruptions and increase the risk of addiction. This ongoing research is allowing researchers to:

- Understand how addictive substances affect the brain’s reward system.

- Develop more effective therapies for treating drug abuse and addiction.

- Establish better methods of detecting people at risk of developing addictions.

Disruption to the brain’s reward system is only part of the reason why drug addictions are so difficult to overcome and why relapses can occur even after years of abstinence. Neuroscientists discovered drugs also alter connections in brain circuits that govern learning and memory, causing the formation of strong associations between the drug’s pleasurable sensation and the circumstances under which it was taken.

One study found when cocaine addicts were shown pictures of drugs for just 33 milliseconds — less time than it takes for the images to enter the addicts’ consciousness — their drug cravings returned. Other research showed when cigarette smokers watched movie scenes of actors lighting up, the brain areas that plan hand movements became more active — as if they were about to light a cigarette themselves. Helping the brain “unlearn” these neurally embedded associations and memories is a major aim of treatment research.

Drugs also disrupt brain circuits involved in impulse control in the prefrontal cortex, making it more difficult for addicts to resist taking drugs. Conversely, research suggests existing deficiencies in prefrontal function increase the risk of drug addiction. This finding may help explain why adolescents are more susceptible to addiction — the prefrontal cortex does not become fully developed until people reach their mid-20s.

Genetics also make some individuals more susceptible to the brain circuit disruptions caused by addiction. There is no single “addiction gene,” but research suggests that up to 60 percent of the vulnerability to addiction may be the result of a complex mix of genetic factors. For example, how an individual responds to nicotine may depend in part on the inherited composition of his or her nicotine receptors. One type of gene variation may alter the receptor composition in a way that increases the risk for addiction, while another variation may decrease it.

Environmental factors, including stress, also disrupt brain circuits in ways that increase vulnerability to drug addiction. Research shows that during withdrawal, the activity of a stress-related neurotransmitter called corticotropin-release factor increases in the amygdala, a brain region that plays a key role in processing emotions — including negative ones like anxiety, depression, and fear. This may explain why addicts often feel anxious and depressed when sober, and why they turn back to drugs so quickly.

However, addicts can recover. Although relapse remains an ongoing threat, the brain has a remarkable ability to mend from drug use. Imaging studies show dopamine levels eventually increase to near normal after months of abstinence. Better knowledge of how addiction disrupts brain circuits — and how genetics and environmental factors influence those disruptions — could help medical professionals develop more effective methods of getting addicts off drugs permanently.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN