Teen Brain Vulnerability Exposed

- Published31 Dec 2011

- Reviewed31 Dec 2011

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

The changes taking place in the adolescent brain lead to increased vulnerability to drug abuse and may also contribute to the emergence of psychiatric disorders.

Experiences mold and change the brain, but never more so than during childhood, when the brain is rapidly building connections between brain cells. This process can be modified by all kinds of experiences, and is called synaptic plasticity.

Although the brain is less “plastic” in adolescence than in childhood, the changes occurring in the teen brain increase its susceptibility to both good and bad stimuli in the environment. Scientific advances are helping researchers better understand this critical time period in development, which often coincides with the emergence of drug and alcohol addiction and the onset of psychiatric disorders.

Reward Hungry

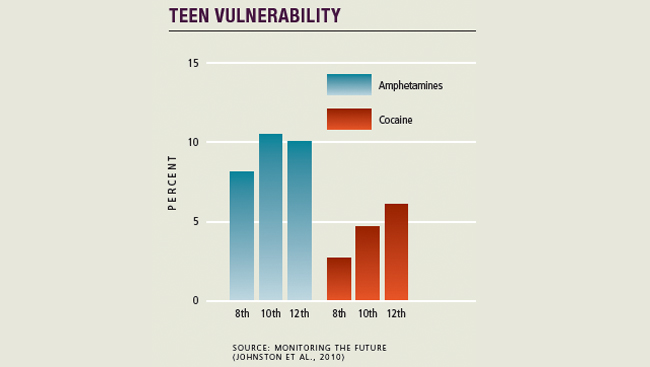

The remodeling of the brain takes place at different stages, with the back of the brain maturing ahead of the front. While the teen brain’s impulse control center has yet to reach full maturity, its reward circuitry is not only ready to go, it is on overdrive, according to a growing body of data. This may help explain why the percentage of teenagers who try an illicit substance more than doubles between 8th and 12th grades, from 21.4 percent to 48.2 percent, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

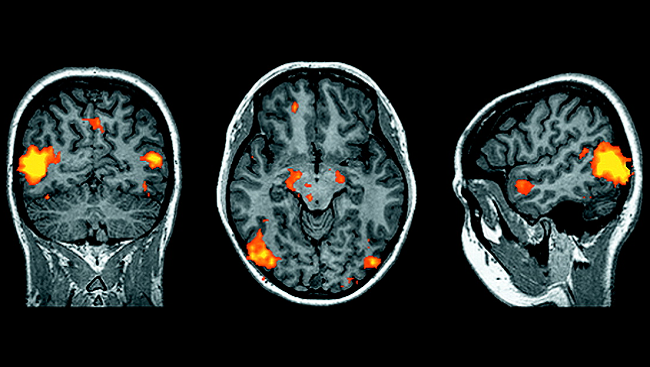

Studies in humans and animals show adolescents react more strongly to reward than adults and children. Teens display greater activity in the nucleus accumbens — a component of the brain’s reward system — than adults or children when completing a simple task for a reward. Neuroscientists believe both the revved-up response to reward and the underdeveloped impulse control center lead teens to greater thrill-seeking.

Animal research suggests drugs and alcohol exploit teens’ weakness to resist rewards, and can lead to changes in the brain that last long into adulthood. Juvenile rats work harder than adults to access drugs like cocaine and amphetamine, and consume more drugs overall. As adults, the rats exposed to drugs as adolescents show memory deficits and permanent changes in brain cells in the reward center.

Exposure to large quantities of alcohol during adolescence can also permanently alter how the body responds to stress during adulthood, other animal studies show. The implications of these findings are particularly disturbing given the prevalence of binge-drinking — the consumption of more than four or five drinks at one time — among teens. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 36 percent of teens aged 18 to 20 reported at least one binge-drinking episode in the previous 30 days.

Troubled Mind

In addition to increased vulnerability to drug and alcohol abuse, mental illnesses often first emerge in the teen years. Neuroscientists continue to look to the changes taking place in the teen brain for clues about why this period often marks the manifestation of mental disorder symptoms, particularly for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

While genetic studies suggest early brain development may play a key role in schizophrenia, some of the symptoms of the disease — such as hallucinations and delusions — often remain hidden until late adolescence or early adulthood.

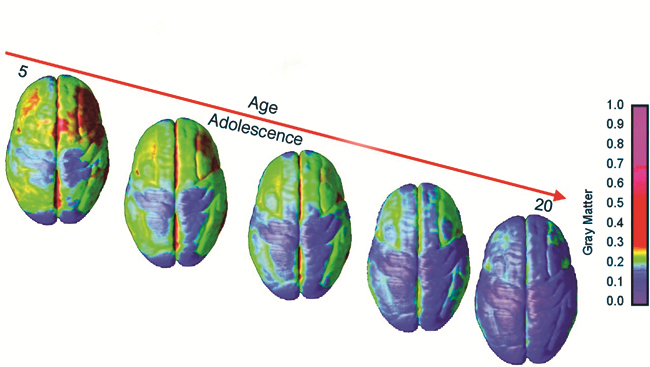

Imaging studies in humans suggest the emergence of schizophrenia may be the result of an accelerated or abnormal pruning of the connections between neurons during adolescence. Children diagnosed with a rare, early onset form of schizophrenia have roughly four times as much pruning of brain cells and their connections during adolescence compared with other teens. Research also suggests that impairments in myelination — the insulation that wraps nerve fibers — in people with schizophrenia could alter the connectivity between regions of their brains. Myelination actively occurs during the teen years.

The ability of researchers to better understand how changes taking place in the teen brain affect mental illness may guide efforts for early intervention and prevention. Similarly, understanding teens’ vulnerability to drugs and alcohol may offer new insights for caregivers and teachers about how to steer adolescents from danger.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN