At Long Last, Medications for Multiple Sclerosis

- Published1 Aug 2012

- Reviewed1 Aug 2012

- Source The Dana Foundation

Individuals with MS should have new hope with regard to treatment advances. For a disease that used to have no medications at all, now more than a half-dozen FDA-approved disease modifying therapies are available.

Ann Romney, wife of the presumptive Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney, recently called the time following her diagnosis of multiple sclerosis in 1998 her "darkest hour." It’s completely understandable since many newly diagnosed individuals feel as if it is an end to life as they know it.

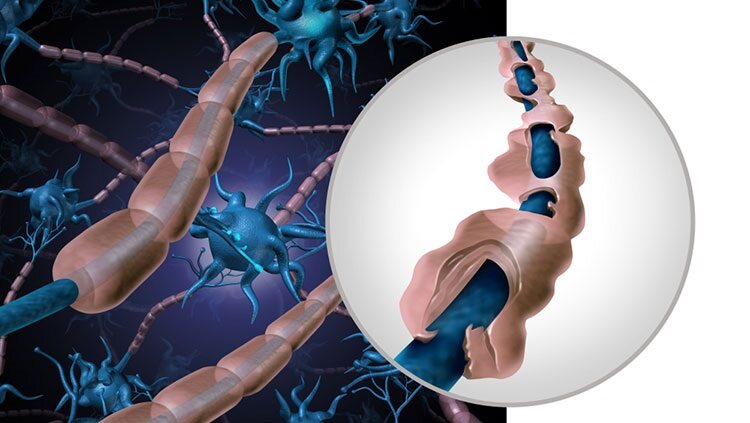

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a common neurologic condition that usually affects individuals between the ages of 15 and 45. It is an autoimmune disease that attacks the myelin sheaths of nerve fibers of both the brain and spinal cord. Women are twice as likely as men to be affected by this disease. About 400,000 people in the U.S. are living with MS and about 200 people are diagnosed each week.

Common symptoms of MS include visual disturbances, dizziness, vertigo, motor weakness, numbness, tingling, gait and balance difficulties, and bowel and bladder impairment. There can be cognitive dysfunction, depression, pain, and fatigue. Most patients with MS have a form of the disease called “relapsing-remitting” or secondary progressive disease; only a fraction have primary progressive MS. Patients with first attacks that do not meet diagnostic criteria for MS are considered to have clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). Early treatment of CIS may prevent progression to MS.

Individuals with MS should have new hope with regard to treatment advances. For a disease that used to have no medications at all, now more than a half-dozen FDA-approved disease modifying therapies (DMT) are available, with the potential to prevent or delay progression. These medications include interferon beta-1b, interferon beta-1a, glatiramer acetate, fingolimod, natalizumab, and mitoxantrone. Long-term follow-up data have shown that treatment with these DMTs reduces relapse rates and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows that they reduce the disease damage to nerve tissue. All these treatments are injectable, except fingolimod (which is taken orally), and generally patients tolerate these treatments well.

The two brands of interferon beta-1b, Betaseron® and Extavia® are taken as an injection under the skin (similar to insulin for diabetes) every other day. Both are approved for CIS and MS. A different interferon, beta-1a, is available in two formulations; one can be injected under the skin, the other into the muscle. The under-the-skin formulation, Rebif®, is taken three times a week, and is approved for MS. The intramuscular formulation, Avonex®, is taken just once a week and is approved for CIS and MS. The most notable side effects of interferon beta include flu-like symptoms, liver enzyme elevations, alterations in blood cell counts, and depression.

Another DMT, glatiramer acetate (Copaxone®), is not an interferon, but a random mixture of four amino acids found in myelin basic protein. It is approved for CIS and MS and its most common side effects include an immediate post-injection reaction, injection-site reactions, lipoatrophy, shortness of breath, and chest pain.

Two treatments, mitoxantrone (Novantrone®) and natalizumab (Tysabri®), have potentially serious (i.e., fatal) side effects. Consequently, they are often used only after other options have failed. One, mitoxantrone, is only rarely used in the United States now because of its cardiac toxicity and the risk of treatment-related acute myelogenous leukemia and myelosuppression. The other, natalizumab, is a monoclonal antibody that blocks the movement of immune cells across the blood–brain barrier into the brain and spinal cord.

Administered intravenously (by vein) every four weeks natalizumab was shown to reduce relapses by 68% in the placebo-controlled phase 3 AFFIRM trial and was initially approved for the treatment of MS in the United States in 2004. During the course of the SENTINEL trial, however, several patients on natalizumab developed an infection of the brain called progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), (caused by a common human virus, the JC virus) that usually leads to severe disability or even death. Natalizumab was temporarily withdrawn from the market in 2005 by the FDA but returned in 2006 with a “black box” warning about the risk of PML. Natalizumab is available only through a special distribution program called the TOUCH™ Prescribing Program.

Earlier this year, the FDA announced that three risk factors appeared to greatly increase the likelihood of Natalizumab-treated patients developing PML : 1) the presence of antibodies in the blood to the JC virus; 2) treatment with Natalizumab for longer than two years; and 3) prior or current treatment with other medications that can weaken a patient’s immune system (immunosuppressants). The FDA also approved a blood test that can tell if a person has been exposed to the JC virus in the past, and their risk of PML.

The first oral DMT for MS, fingolimod (Gilenya™), was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2010. It is a new class of medication, thought to work by attaching to the surface of immune cells and trapping them in lymph nodes, thereby preventing them from attacking cells in the central nervous system. Taken once daily, it was shown to reduce annualized relapse rates by about half in phase III clinical trials. However, a number of safety concerns have developed, particularly cardiac, including slowing of heart rate and heart block, an electrical problem affecting the rate and rhythm of heartbeat. In April 2012, the FDA revised the prescribing information for fingolimod to clarify who should avoid use of fingolimod and to provide additional guidance on first-dose monitoring. In addition, with fingolimod, there is the risk of swelling in the eye affecting vision (macular swelling), cough, elevation of liver enzymes, and significant lowering of white blood cell counts. Thus, additional requirements prior to starting fingolimod include blood tests to determine the white blood cell count, liver functioning, and previous exposure to chickenpox; in addition to an ophthalmologic (eye) exam.

And at least half-dozen more disease-modifying treatments for MS are on the way. Investigational drugs include several oral small molecules either currently under review by the FDA or likely to be submitted soon and as many as four monoclonal antibody drugs. Among all these are two existing drugs, already on the market for other diseases, which have performed well in clinical trials for MS and a new BG-12 is an oral form of dimethyl fumarate, the second-generation of a compound, fumaric acid that has been used in psoriasis since the 1950s. It is thought to decrease oxidative stress and inflammation. Currently under review by the US FDA for MS, BG-12 significantly reduced the proportion of people with MS who experienced relapses in a study of more than 1200 people with relapsing-remitting MS and significantly reduced the average number of annual MS relapses in another trial of more than 1400 people with relapsing-remitting MS. The most common side effects with BG-12 included flushing, or reddening of the skin, and gastrointestinal issues such as diarrhea and nausea.

Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada™; also marketed as Campath©) is currently approved for the treatment of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. It is a monoclonal antibody that targets a protein on the surface of immune (T and B) cells and is given intravenously for 3 to 5 days once a year. In one clinical trial, it significantly reduced relapse rates when compared with Rebif® (interferon beta-1a). In another, alemtuzumab significantly reduced relapse rates and worsening of disability, also compared with Rebif®, in 840 people with relapsing MS who had relapsed while on therapy. Side effects of concern include significant thyroid-related problems and a blood clotting disorder (idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, or ITP) that was fatal in one case. Other common adverse events included reactions associated with intravenous treatment (such as headache, rash, fever, flushing, hives and chills). The manufacturer has submitted alemtuzumab for approval in the US and Europe.

Teriflunomide (Aubagio™) is a once-daily oral disease-modifying drug that is under investigation for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS. It is thought to block the proliferation and functioning of activated immune cells. In a study reported in 2011, Teriflunomide reduced the average number of MS relapses and disease activity on MRI scans significantly more than placebo in 796 people with relapsing forms of MS, and, in another involving 1,169 people, it reportedly reduced relapses compared with placebo over at least 48 weeks. However, still another found it did not outperform one of the interferon drugs when it came to treatment failure. At least two other phase III studies of Teriflunomide are ongoing. The most frequent side effects reported for Teriflunomide include headache, increased liver enzymes, nausea, diarrhea and thinning of the hair. An application for marketing approval of Teriflunomide has been accepted for review by US and European authorities.

So, how then do clinicians and MS specialists decide which treatment is “best’ for their patient with MS? First, and foremost, it is important to state that there is very little well-designed comparison trial data to help decide which, if any, of these drugs is the superior option. Many factors go into choosing which medication to start for an individual patient and very little consensus among MS experts. I suspect that most consider disease stage and severity; medical history and other medical problems their patient might have; patient preference regarding injections and injection frequency; impact of side effects; safety/monitoring requirements; and financial, including health insurance, considerations.

Our work is not done. For many clinicians, the injectable interferons and glatiramer acetate (so called “platform therapies”) are probably used first-line to preserve treatment options for the future. The other drugs I’ve described are generally second-line therapies because of side effects. Whatever the drug, unfortunately, many MS patients experience relapses or show evidence of further deterioration despite these treatments. And more painfully for all of us who study and treat MS, and for our patients even more, the biggest challenge in MS treatment today continues to be with primary progressive MS, where the currently available DMTs, which largely target inflammation, are not effective.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

The Dana Foundation is a private philanthropic organization that supports brain research through grants and educates the public about the successes and potential of brain research.