How Smartphones Hijack the Brain

- Published8 Jan 2021

- Author Charlie Wood

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Each year, young adults spend more and more time on their smartphones. In 2018, they averaged 3 hours and 40 minutes engrossed in their devices each day. In 2019 that figure climbed to 4 hours and 30 minutes. According to research by Larry Rosen, Professor Emeritus at California State University, Dominguez Hills. This year they’re on track to break five hours.

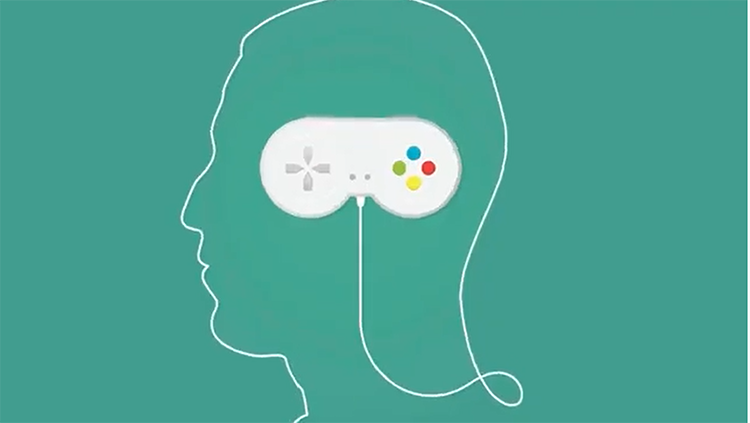

“It’s become kind of an appendage to people,” Rosen says.

He suspects the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated the trend. But, its roots trace back to the addictive nature of the devices. Largely by design, the features that make smartphones convenient and fun also let them hijack the brain’s reward and attention systems.

Addictive by Design

Enjoyable activities, from watching Netflix to gambling, switch on the brain’s “reward pathway,” flooding the brain with the feel-good chemical messenger dopamine. Any dopamine-producing activity can lead to “behavioral addiction,” when a person feels compelled to engage in a behavior to the point that it hurts their health, work, or relationships. (The same mechanism drives drug addiction, but is distinct from drug dependence, when a person’s body comes to physically rely on a substance).

Smartphone use falls into that category, according to psychiatrist Anna Lembke, Chief of the Stanford Addiction Medicine Dual Diagnosis Clinic. Texting friends, swiping dating profiles, even checking email, can all be engaging enough that they keep bringing users back for more. “That’s the hallmark of an addictive drug,” Lembke says. “It just intrinsically draws people in.”

Services like Facebook and YouTube leverage our attention and engagement to sell ads or otherwise attract funding. “It’s happening not by accident, but by design,” said Tristan Harris, a former Google design ethicist who co-founded the Center for Humane Technology, during testimony before the Senate Commerce Committee in 2019. “The business model is to keep people engaged.”

To attract and hold attention, app engineers employ techniques familiar to anyone who’s set foot in a casino. One strategy is to remove cues that might wake a user from their reverie. Where casinos lack clocks or windows, social feeds lack bottoms. “If I take the bottom out of the glass,” Harris said, “you don’t know when to stop drinking.”

Harris also cites the “pull to refresh” feature, which may or may not reward the user with new email messages or Instagram photos. In pathological gamblers, uncertainty drives bigger dopamine spikes than money. That is, anticipating a reward is more enjoyable than actually receiving the reward. A similar mechanism may be at play when smartphone users refresh an app, betting seconds of their time on the possibility of new content.

Similarities extend even to appearance. Like casinos, home screens are bright and colorful. And red — the most physiologically arousing of the primary colors — abounds, thanks to omnipresent notification badges. A smartphone has the “flashing lights, the colors, the whistles and bells,” Lembke says. “Even when we try to disengage, it’s hard.”

Attention Deficits

While smartphone use can become problematic, behavioral addiction falls on a spectrum. Like watching TV or even gambling, most people can indulge in moderation without any adverse effects.

Still, there are good reasons to disengage. In 2014, neuroscientist Abraham Zangen took advantage of a brief window at the dawn of the smartphone era to compare smartphone-owning college students with students who hadn’t yet adopted the technology.

The heaviest users had more trouble focusing than non-users, scoring roughly five to ten percent higher on tests of attention deficit disorder. They also had diminished activity in the right prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain that regulates attention and self-control. Structural changes in this area have been linked with ADHD.

“Your attention is being distracted very, very often,” says Zangen, a professor at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel.

The Rules of Disengagement

By offering unlimited communication, knowledge, and entertainment literally at the tap of an icon, smartphones have become essential appliances for billions of people. The question users now face is how to leverage the devices’ perks while minimizing the penalties.

To disengage from devices, advice varies. One strategy is to de-casino the phone as much as possible. Many experts recommend turning off all nonessential notifications, for instance, or even stripping the screen of color to make the device less appealing.

Lembke recommends periods of total abstinence — up to a month if possible, but at least one day a week. She believes such phone vacations might “reset” the reward pathway, letting our brains recover from technology’s easy and regular dopamine hits, at least for a time.

But reports of effectiveness are entirely anecdotal. Rosen has been studying various strategies with his students, such as disabling notifications for social media and hiding addictive apps. But the gains are modest, he says, and evaporate when the students resume normal use.

To Lembke, the greatest danger of smartphones isn’t impaired attention or behavioral addiction but how the devices keep us from “being fully present for the people around you, whether it’s at a meal or a meeting or with your children,” Lembke says. “I think there’s a slow erosion of human connection.”

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). The Emerging Neurobiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Association Cortex. The Journal of Pediatrics, 154(5), I-S43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.018

Hadar, A., Hadas, I., Lazarovits, A., Alyagon, U., Eliraz, D., & Zangen, A. (2017). Answering the missed call: Initial exploration of cognitive and electrophysiological changes associated with smartphone use and abuse. PLOS ONE, 12(7), e0180094. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180094

Jacobs, K. W., & Hustmyer, F. E. (1974). Effects of four psychological primary colors on GSR, heart rate and respiration rate. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 38(3, Pt. 1), 763–766. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1974.38.3.763

Linnet, J., Mouridsen, K., Peterson, E., Møller, A., Doudet, D. J., & Gjedde, A. (2012). Striatal dopamine release codes uncertainty in pathological gambling. Psychiatry Research, 204(1), 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.04.012

Zou, Z., Wang, H., d’Oleire Uquillas, F., Wang, X., Ding, J., & Chen, H. (2017). Definition of Substance and Non-substance Addiction. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 1010, 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5562-1_2