Do Antidepressants During Pregnancy Affect Fetal Brain Development?

- Published8 Oct 2019

- Author Lindzi Wessel

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

A.H. knew she wanted to be a mother long before she had any concrete plans to get pregnant. But she wanted to be ready, so early on, she asked her primary care physician about what antidepressants were safest for a developing baby. The answer was like a slap in the face. None, said her doctor. To have a safe pregnancy she should stop all treatment.

A.H., who had dealt with severe depression most of her life, spent the next year thinking she could never have a baby. When she once stopped her medications at 26, she wound up hospitalized, in severe emotional pain, and strongly entertaining thoughts of suicide. She knew it would be too risky to try to do that again.

“To hear that that was the condition I would have to be in in order to have a child really took that off the table for me,” she says. “It was deeply upsetting.”

But the information A.H. got from her doctor was based on problematic misconceptions, says Lauren Osborne, a reproductive psychiatrist at Johns Hopkins Medicine. Osborne regularly encounters women who have been counseled either to stop taking antidepressants or not to start the drugs if they become depressed or anxious while they’re pregnant. “Someone has told them they need to stop all medications during pregnancy, and they wind up in my office in great distress,” she says.

The concern about antidepressants stems from the potential of the mood-altering chemicals to interfere with development of the fetal brain. Available evidence, however, suggests the risks are minimal. And, some experts argue they pale in comparison to the risks associated with not treating depression and anxiety.

The most commonly prescribed type of antidepressants — selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs — target the mood-regulating neurotransmitter serotonin. Low levels of serotonin, which is involved in cognition, appetite, and sleep, have been linked to depression and anxiety. SSRIs block the molecular vacuum cleaners that suck up excess serotonin from the spaces between neurons, leaving more serotonin available to act on neurons.

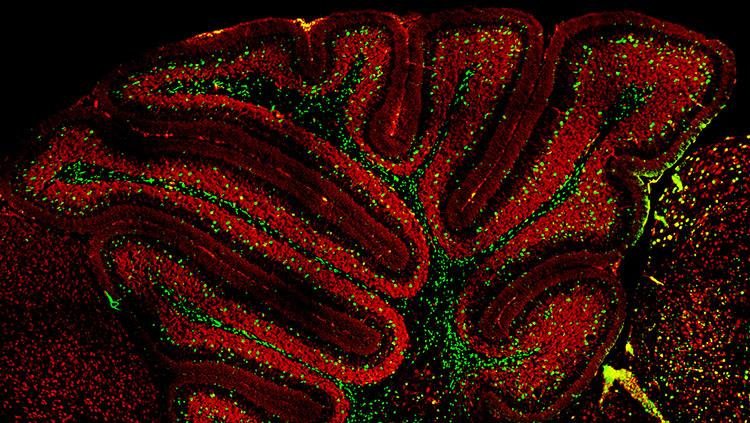

That’s good for a depressed brain — but some worry it could be risky for the developing fetal brain. Serotonin helps coordinate the formation of neuronal processes and their connections in the developing nervous system. SSRIs can cross the placenta, and research in mice shows the young brain is sensitive to SSRIs: mice exposed to SSRIs early in life have shorter dendrites with fewer branches, and they show more anxiety- and depression-like behaviors as adults.

Numerous epidemiological studies have also pointed to an array of possible risks, ranging from heart defects to learning disabilities to autism. But the evidence tends to be thin, says Osborne. Early studies often didn’t account for the fact that maternal depression itself carries increased risks for mom and baby.

“People with depression have higher rates of obesity, higher rates of C-section, preeclampsia, diabetes, smoking, substance use — all these things may also affect what’s going on in pregnancy,” says Osborne.

Particularly for more severe issues, like autism, some recent studies using more advanced statistics to make sure groups are comparable suggest concerns may be unfounded, she says.

While the risks of SSRIs remain disputed, researchers know leaving depression untreated during pregnancy carries risks. Depression during pregnancy is one of the strongest predictors for postpartum depression. Both degrade social interactions, interfere with work, worsen general health, and are linked to higher suicide risk. Depressed, expectant moms are less likely to get enough sleep, make it to medical appointments, and avoid drugs and alcohol — all critical behaviors for a healthy pregnancy. Biological changes accompanying depression, like high levels of stress hormones, may also impact the health of the developing baby.

“Most of the drugs we have in psychiatry are actually relatively safe in pregnancy,” Osborne says. “But there’s a huge amount of attention paid to the very small risk that exists and no attention paid to the risks to the woman and the child of stopping the medication.” A.H. eventually found a doctor who told her about such risks, encouraged her to keep taking medication, and, when she started struggling in her second trimester, referred her to a reproductive psychologist — something A.H. never knew existed — to adjust her treatment plan. A.H., whose son is now 18 months old, feels lucky to have had the resources to seek specialized care.

“It’s something that should exist across the board,” she says.

Physicians can help patients navigate the challenge of carefully balancing risks. How they talk to their patients is critical, says Alice Panchaud, a pharmacoepidemiologist at the Harvard School of Public Health. Health risks are often presented as relative instead of absolute risks, meaning a threat might sound a lot more likely than it actually is. Some studies, for example, suggest SSRIs might double the likelihood of a condition called persistent pulmonary hypertension. Yet, the baseline risk in newborns is only 0.2%, so a two-fold increase still translates to only a 0.4% absolute risk. When Panchaud talks to her patients, she tries to flip the numbers around, speaking instead about the likelihood of having a healthy child.

“This is how you have to talk to the patient: Instead of a 98 percent chance of a healthy baby you might have a 97.5 percent chance,” she says. “You try to put the facts on the table, so they stop seeing only the risks but also the benefits.”

A.H. requested we not use her full name.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Ornoy, A. (2017). Neurobehavioral risks of SSRIs in pregnancy: Comparing human and animal data. Reproductive Toxicology (Elmsford, N.Y.), 72, 191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.05.003

Rebello, T. J., Yu, Q., Goodfellow, N. M., Caffrey, M. C., Teissier, A., Morelli, E., … Ansorge, M. S. (2014). Postnatal day 2 to 11 constitutes a 5-HT-sensitive period impacting adult mPFC function. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34(37), 12379–12393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1020-13.2014

Rotem-Kohavi, N., & Oberlander, T. F. (2017). Variations in Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Children with Prenatal SSRI Antidepressant Exposure. Birth Defects Research, 109(12), 909–923. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1076

Wang, S., Yang, L., Wang, L., Gao, L., Xu, B., & Xiong, Y. (2015). Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and the Risk of Congenital Heart Defects: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Journal of the American Heart Association, 4(5). doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001681

Weisskopf, E., Fischer, C. J., Bickle Graz, M., Morisod Harari, M., Tolsa, J.-F., Claris, O., … Panchaud, A. (2015). Risk-benefit balance assessment of SSRI antidepressant use during pregnancy and lactation based on best available evidence. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety, 14(3), 413–427. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2015.997708