Fear Conditioning: Processing and Forming Fears

- Published22 Feb 2024

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Fear plays an essential role in helping us know when it’s time to get out of a sticky situation. Yet not everything we fear is life-threatening. That’s because fear can also be taught through conditioning, a process by which our brains associate a sound, sight, or other sensation with imminent danger. Take quacking. Most of us don’t have a deep-set fear of ducks. But get shot by a nerf-gun enough times while someone plays a recording of quacking, and you may just learn to make a run for it when you hear a duck approaching.

This is a video from the 2023 Brain Awareness Video Contest.

Created by Shannon Riley.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

[Screams] Ahh!

Fear: What is it? How are they formed? Can we get rid of our fears? And what is going on in the brain while all this happens? First, let's define fear.

Fear is a primitive emotion resulting in a set of functional changes triggered by perceived imminent threat. Some of these functional changes include rapid heart rate, shortness of breath, nausea, tensing of muscles, and pupil dilation, which have all been elicited in the fight-or-flight response, preparing our body to fight or flee a fearful stimulus.

From an evolutionary perspective, the main purpose of fear is to promote survival. Those that feared the right threat survived, reproduced, and passed their fear to their offspring. Those that didn't fear the right threats — well, I think you know what happened. So, the question remains: What is going on in the brain to trigger these fear responses?

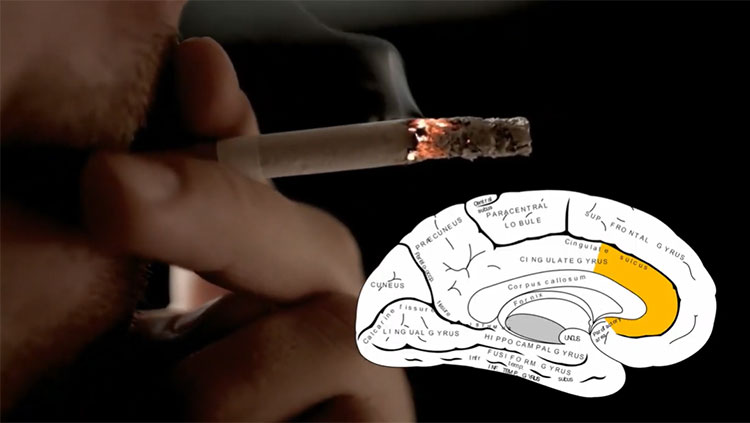

Our answer lies with the amygdala. Found in the middle of the brain towards the top of the temporal lobe, the amygdala is the brain's main center for emotion regulation and is specifically associated with processing fearful stimuli.

Structurally, the amygdala is made up of several groups of nuclei, some of which are included in this diagram. In the presence of a fearful stimulus, sensory areas of the brain provide information to the input area of the amygdala. Once processed, the output areas of the amygdala send signals to the hypothalamus, triggering the release of cortisol, our body's main stress hormone, and the activation of the autonomic nervous system, the body's unconscious system that regulates things like heart rate, digestion, and respiration.

Both prepare our bodies to fight or flight and are responsible for the production of fear responses. So far, we've explained why someone may fear a stimulus that poses a threat to survival. However, this does not explain why someone may have a fear of something unthreatening. Let's say, ducks. But classical conditioning may have the answer.

In the context of fear, classical conditioning is mainly conducted on rats. A typical experiment will involve an unconditioned stimulus, a painful shock that produces an unconditioned response, a fear response. A neutral stimulus, a tone, is also presented, producing no response. When a painful shock is paired with a tone, a fearful response is produced.

Over time, the repetition of this pairing will result in the rat producing a fearful response to the now conditioned tone alone, resulting in a conditioned response. However, can this be applied to humans? Let's find out using our unsuspecting subject, replacing the shock with being shot and the tone with quacking to classically condition the fear of ducks.

First, we will present the subject with the unconditioned stimulus alone. Next, we will present the subject with a neutral stimulus alone. Excellent. Our subject is responding to the unconditional neutral stimuli in a way we would expect. Now we will repeatedly pair these stimuli together.

Let's see if we have classically conditioned the fear of ducks by presenting our subject with a now conditioned stimulus to observe if a fear response was formed. It would appear we've managed condition of fear of ducks into our subject. But what is going on in the brain to form this conditioned fear? Let's go back to the amygdala to find out.

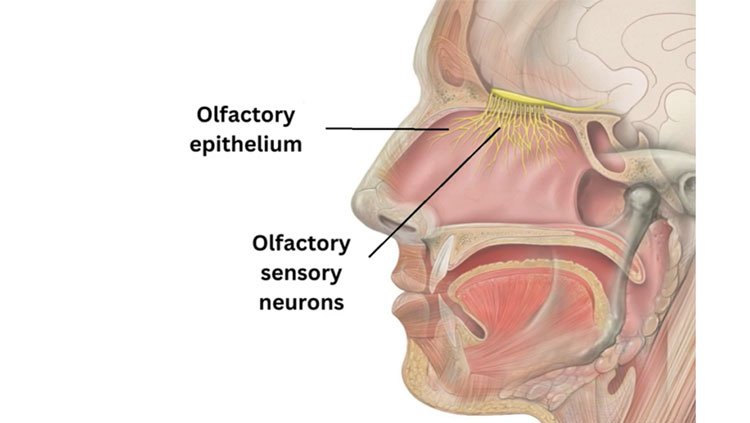

In the presence of unconditioned stimulus, signals from sensory areas of the brain are strong enough to activate the amygdala and trigger a fear response. In the presence of a neutral stimulus, the signals from sensory areas of the brain are not strong enough to activate the amygdala. Therefore, produce no fear response. When the unconditioned and neutral stimuli are repeatedly paired, a fear response is produced as synaptic connections between sensory areas and the amygdala becomes stronger, making it easier to send a signal that results in a fear response.

Now, when the newly conditioned stimulus is presented, the synaptic connections are so strong and sensitive, the signal produced is able to activate the amygdala alone producing a fear response. So, if we can condition a fear, does this mean we can get rid of it? Many clinical therapies for phobias are based on classical conditioning, one of the most prominent being “flooding.” This involves the patient confronting their fears, aiming to break the bond between the conditioned stimulus and response, as over time the patient realizes that the fearful stimulus does not pose a threat and begins to relax.