Waking Up With A Foreign Accent

- Published26 Jul 2017

- Reviewed26 Jul 2017

- Author Jessica P. Johnson

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Foreign Accent Syndrome is a rare condition that alters the speech centers of the brain. The result: altered speech patterns that make it sound like one speaking with a foreign accent. To find out more about this mysterious condition, listen to this podcast from BrainFacts.org.

Music by Josh Woodward, used under a creative commons license.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

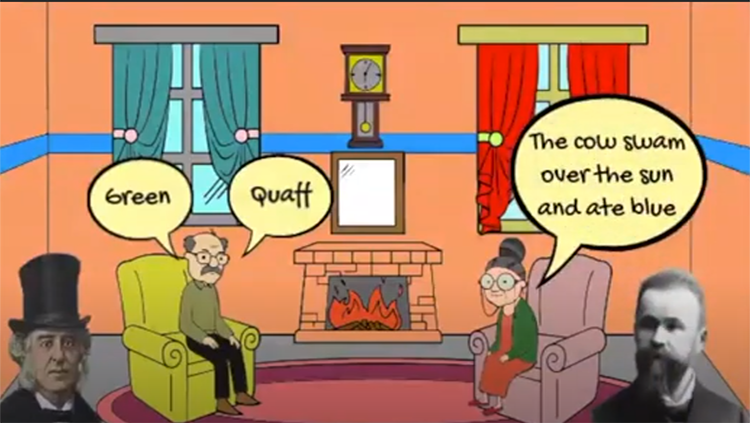

You may remember hearing news stories about a person suddenly developing a foreign accent or the ability to speak a new language fluently. The truth is, these reports are misrepresentations of an extremely rare condition called Foreign Accent Syndrome, or FAS. Only 100 cases of the condition have been reported in the scientific literature since its discovery a century ago. FAS is neither a foreign accent nor a newly acquired language. Instead, it is a sudden alteration in a person’s speech patterns due to injury to the brain’s speech centers, which gives the impression of a foreign accent.

Ryalls: Cases of people speaking another language are not Foreign Accent Syndrome. In no case that I know of, or have come across, or had experience with has a person suddenly acquired the ability to speak a different language. I know of no case where that has happened.

SfN: Jack Ryalls is a professor of Communication Sciences & Disorders at the University of Central Florida. He has helped diagnose patients with FAS and, along with colleague Nick Miller at Newcastle University in the UK, has recently collected personal testimony from 27 patients with the syndrome. One patient they worked with suffered a traumatic brain injury, or TBI, in a car accident. Before the accident, the woman, who grew up in Michigan, spoke with an American accent. Afterward, she sounded like this:

FAS Patient: You wish to know all about my grandfather. Well, he is nearly 93 years old, yet he still thinks as swiftly as ever.

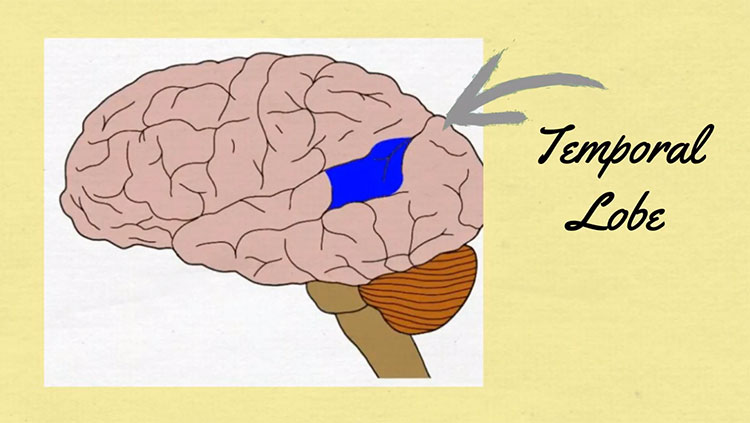

SfN: What accent does this sound like to you? Patients with FAS have reported being asked whether they’re German, French, English, Chinese, and many other nationalities. But the accent you hear actually results from damage to the language centers of the brain’s left hemisphere and related brain regions which control the muscle movements used to create speech.

Ryalls: They’re still arriving at perfectly fluent speech, but with different muscular activation patterns.

SfN: In addition to traumatic brain injury, patients have developed FAS after strokes, severe migraines, or brain lesions that arise due to developmental abnormalities. These events impair movements of the tongue, lips, and jaw, and can change the way a person pronounces vowels and controls pitch and inflection.

Ryalls: There seems to be two schools of accents that people acquire. One is the up and down, rounded vowels, and vowel articulation that sounds a little bit Swedish or Scandanavian. And then the other school, if you will, of accents is the dropping of article and preposition and it lends to the accent of eastern Europeans because, for example in Russian, they don’t use the articles and the prepositions. So it sounds eastern European.

SfN: Because FAS is so rare and the causes and symptoms wide-ranging, the specific brain regions affected are still being teased out.

Ryalls: In general, it is more a preponderance of damage to the left hemisphere of the brain. And it seems to be more in the pathways that coordinate sub-cortical areas of the brain than it is with the cortical areas of the brain for speech and language. And this may be simply because there is more neural traffic going on in the subcortical areas of the brain that are trying to coordinate respiration and rhythm and all of the things we have to bring to bear in speech production.

SfN: Recent studies also indicate a possible role of the cerebellum in FAS. Located near the base of the skull, the cerebellum controls motor function. Brain scans of some FAS patients have revealed a disrupted neural connection between the cerebellum and the brain’s speech centers.

The rarity of FAS also makes it difficult for doctors to diagnose, leaving many patients struggling to make sense of their new accents and sometimes suffering social isolation as a result. In one famous case, a Norwegian woman who developed FAS after suffering a shrapnel wound to her brain’s left hemisphere in a Nazi attack during WWII was ostracized by her community.

Ryalls: Part of her problem was that she wasn’t able to produce the tone accents of Norwegian. And so people took her as a German collaborator hiding out among the Norwegians and they refused to serve her in the local shops.

SfN: The good news is that between 20 and 50 percent of FAS patients naturally recover their normal accents after trauma. In contrast to other speech disorders, FAS impairments appear to be mechanical rather than cognitive, and according to Ryalls, may represent a stage in the brain’s process of recovery from injury.

Ryalls: I can go as far as to speculate that people who acquire it from TBI are more likely to recover than people who get it from stroke or more permanent, devastating effects of brain damage.

SfN: But so far, therapies to speed up recovery of patients’ normal accents have had limited success.

Ryalls: There’s very limited attempts to do therapy in the traditional sense of the term speech-language pathology with patients with Foreign Accent Syndrome. The person has to have a voluntary or conscious control to a certain point over their speech patterns in order to change them. And that’s typically not the case with Foreign Accent Syndrome.

SfN: For those who don’t recover their normal accents, Ryalls says that accepting the new accent gives patients the best chance of reclaiming their normal lives. And with increased recognition and improved diagnosis of the syndrome, he is hopeful that research will eventually catch up and uncover new therapies for patients with FAS.

Ryalls: I believe in my heart of hearts that all the cases of Foreign Accent Syndrome are due to an organic place in the brain that has brain damage and that we’re just not seeing it yet. There is a technique known as diffusion tensor imaging and that allows us to view the connections between areas of the brain that isn’t really viewable in standard imaging techniques. I believe that eventually we’ll have even more dialogue between the imaging people and the people who are studying the effects of the brain damage. I believe that’s probably going to show us a lot more disruptions of transmission between or communications between areas of the brain than are presently known and viewable.

SfN: Thanks for listening. Check out more information about how our brains produce our unique patterns of speech at BrainFacts.org.