Your Cursing Cortex

- Published10 Jul 2019

- Author Charlie Wood

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

While conducting fieldwork in the late 1980s in Fargo, Diana Van Lancker Sidtis, a neurolinguist, encountered a striking phenomenon. A North Dakota farmer had been left unable to speak by a stroke — a condition called aphasia. And while he couldn’t discuss the weather or name the day of the week, he did manage to make political critiques of the president with the help of a special type of word.

“Sometimes when I passed him in his wheelchair in the hall and whispered, ‘Ronald Reagan’ in his ear, he would smile and respond, ‘goddammit,’” Sidtis remembered. While Sidtis observed this in the 1980s, scientists have noted this phenomenon for centuries, including eminent neurologist Paul Broca known for his research on a region of the frontal lobe that would later be named Broca’s region. In 1861 Broca reported a patient who retained “Sacre nom de Dieu,” or the ability to curse, despite the loss of productive language capacity.

While cursing plays a crucial role in many, if not most people’s linguistic lives, the phenomenon has been slow to attract academic attention. Offensive words don’t lend themselves to grant proposals, and the startling circumstances eliciting taboo exclamations don’t exactly occur on command. “It’s hard to put somebody in an MRI and say, ‘Hey swear,’” says Tim Jay, a cognitive psychologist emeritus at the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts. “That’s not spontaneous.” You might be able to coax out a four-letter word or two, but without the emotional context that accompanies the discovery of a freshly cracked phone screen or missing wallet, full throated expressions of discontent typically remain elusive.

Instead, researchers have cobbled together observations of patients who’ve lost the ability of normal speech and those with disorders that make them occasionally feel compelled to curse, with experimental participants exposed to foul language, inferring that not all parts of speech are created equal. Curses may mingle with polite nouns and verbs in our mouths, but they get special treatment in the brain. Bridging our animalistic and enlightened natures, the just-stubbed-your-toe howl is as much physical action as it is linguistic message.

Verbal Weapons

Sidtis spent the ’90s studying a range of aphasia-related effects but found the types of speech often left intact after a stroke — swearing and other routine phrases — especially fascinating. One clue to what sets these words apart sent her on an academic detour through Tourette Syndrome (TS), a disorder where people involuntarily display quick, repetitive movements such as shrugging their shoulders or grimacing. Crucially to Sidtis, a minority compulsively shout obscenities, but not similar sounding words. One early hypothesis suggested that the brain might be retrieving simple sounds at random, but through a laborious letter writing campaign soliciting examples from researchers worldwide, Sidtis showed in 1999 that the process couldn’t be arbitrary: From Spain to Sri Lanka, people with TS that have cursing episodes spout only offensive terms.

Something in the brain must lump indecent words in with actions to let the TS affected mind make these choices. And to anyone who’s ever experienced the emotional catharsis of a good cussing, the notion that using strong words could feel something like punching a pillow won’t come as a total surprise. “[Dropping an F-bomb] is almost like a behavior, a physical act,” Jay says.

[Dropping an F bomb] is almost like a behavior, a physical act.

The common denominator is a brain area known as the basal ganglia, which supports everyday movements like walking and typing. People with TS appear to have too many commands executing in the basal ganglia. Since TS can trigger swears as well as eye rolls, the brain likely stores both items similarly — as an indivisible unit of action. “The fact that [epithets] are overlearned as a whole chunk makes them completely different from something that’s grammatically produced,” Sidtis says.

Those on the receiving end of an F-bomb process it differently too, in a way with both emotional and physical effects. Twists on the classic Stroop color test, which challenges participants to ignore the meaning of a printed word and name only its color, have shown that people take longer to get through an NSFW (Not Safe For Work) list than they do with lists of neutral words (banana), or even emotional words (death). The slow down happens because an ancient part of our brain, the almond-shaped amygdala, can’t help but register curses as threats.

“If the word is taboo or offensive, that automatically triggers a reaction in the amygdala,” says Donald MacKay, a cognitive psychologist at UCLA. Buried deep, just above the brainstem, the amygdala is involved with strong emotions, especially fear and threat detection. After encountering a swear this structure sounds the alarm, making your brain work overtime to scrutinize the situation. You even break out in a light sweat.

And the effect goes the other way too, according to MacKay, with certain feelings launching expletives. “When you get that pattern of emotion that you experience when you hear **** or ****, that same pattern of emotion will tend to trigger one or the other of those two words.”

Both the amygdala and the basal ganglia reside in the evolutionarily older core of the brain, below the intricately folded cortex associated with many of humanity’s newer talents. Cursing’s direct line to this primitive area leads some researchers to speculate that the practice shares similarly ancient origins. When a cat’s amygdala finds a threat, its basal ganglia sets off a rage-driven hiss or scratch. Perhaps the same circuit in our brains releases obscenities instead. “This is the neat thing for humans,” Jay says. “There’s that link between the lower brain and language.”

Customized by the Cortex

Yet the enraged ranting of a taxi driver is more complex than a bestial roar. Your word of choice when you hit your funny bone may differ from what you shout when cut off in traffic, and both certainly differ from the words a Mongolian versus a Latvian speaker would spout in those situations. Cursing somehow manages to be both instinctive and contextual.

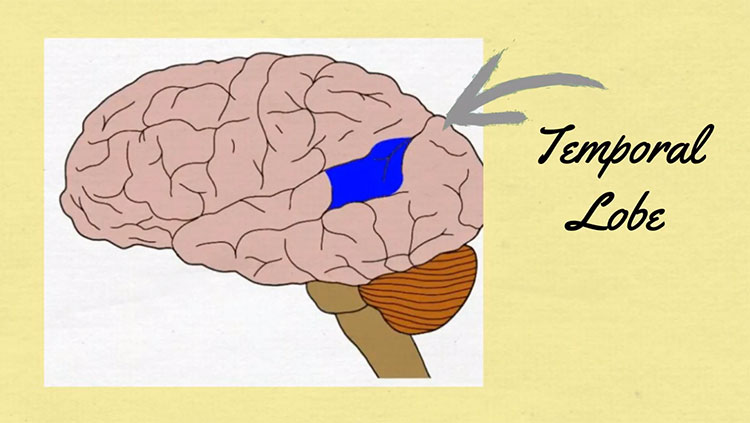

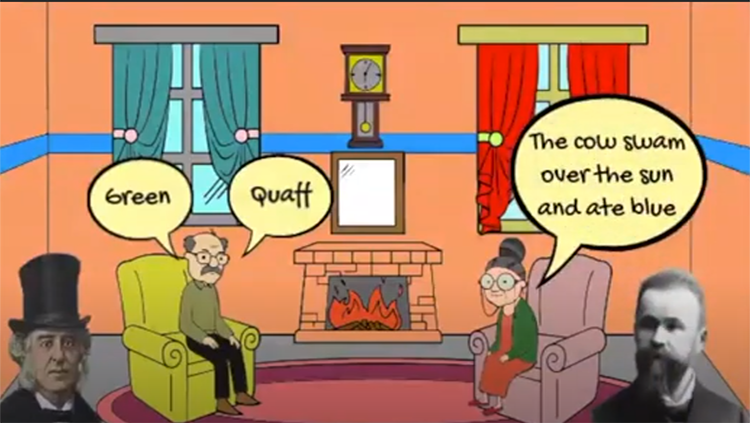

The key lies in the cortex. After the amygdala and basal ganglia launch the emotional attack, it passes through centers of higher thought before execution. Speaking tends to be a left hemisphere affair, as expressive aphasia demonstrates when a stroke damages the left and robs a person of their gift of gab while leaving their listening skills intact. As Sidtis and others have observed, however, these people can often still swear, which suggests that a sailor’s tongue resides on the right.

Why distribute different skills around the cortex? Because the right hemisphere specializes in handling chunks of meaning, Sidtis says, while the left side is better at breaking down complex objects into parts. She now proposes a two-part model of speech where the left deals with novel sentences, while the right takes care of common units of speech like cursing, as well as counting, and reciting days of the week, and a host of other fixed verbal expressions, all of which have been preserved in people with aphasia. In other words, the right hemisphere processes a different kind of language. There are many unanswered questions that remain. Rosemary Varley at University College London agrees that this is a very important topic to explain but questions whether we should expect to observe changes in swearing when the right hemisphere is damaged, in other words the case of the swearer who stops cursing.

Of course, the practice of swearing enjoys a cognitive and cultural diversity that runs the gamut from a grimaced yelp to a honed punchline, so your cortex likely stores your favorite cuss in various locations. Hammering your thumb might trigger a copy on the right while spelling it out could access a version on the left, with other situations requiring some blend of these, or other circuits. With profanity research in its infancy, the simple words still hide plenty of secrets.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Discussion Questions

- Why is it difficult to study swearing?

- How have scientists found ways to study cursing?

- What role do the basal ganglia and the amygdala play in speech and cussing?

References

Bowers, J. S., & Pleydell-Pearce, C. W. (2011). Swearing, Euphemisms, and Linguistic Relativity. PLOS ONE, 6(7), e22341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022341

Jay, T. (2000). Why we curse: A neuro-psycho-social theory of speech. Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Van Lancker, D., & Cummings, J. L. (1999). Expletives: neurolinguistic and neurobehavioral perspectives on swearing. Brain Research Reviews, 31(1), 83–104. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00060-0

Mackay, D. G., Shafto, M., Taylor, J. K., Marian, D. E., Abrams, L., & Dyer, J. R. (2004). Relations between emotion, memory, and attention: Evidence from taboo Stroop, lexical decision, and immediate memory tasks. Memory & Cognition, 32(3), 474–488. doi: 10.3758/BF03195840

Pinker, S. (2010). “The Seven Words You Can’t Say on Television.” The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature. Penguin Books.