The Curious Case of Patient H.M.

- Reviewed28 Aug 2018

- Author Deborah Halber

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

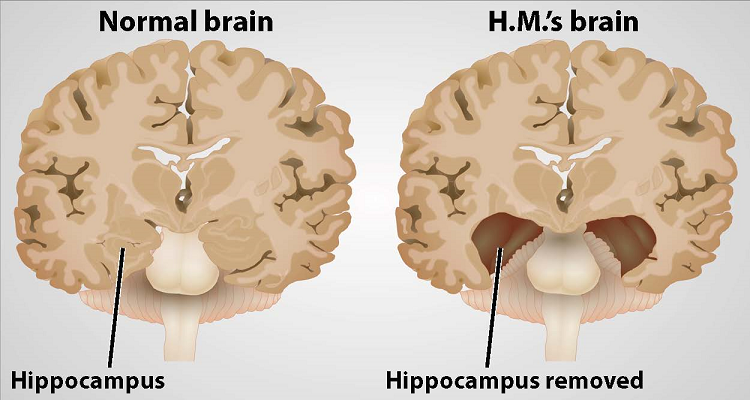

On September 1, 1953, time stopped for Henry Molaison. For roughly 10 years, the 27-year-old had suffered severe seizures. By 1953, they were so debilitating he could no longer hold down his job as a motor winder on an assembly line. On September 1, Molaison allowed surgeons to remove a thumb-sized section of tissue from each side of his brain. It was an experimental procedure that he and his surgeons hoped would quell the seizures wracking his brain.

And, it worked. The seizures abated, but afterwards Molaison was left with permanent amnesia. He could remember some things — scenes from his childhood, some facts about his parents, and historical events that occurred before his surgery — but he was unable to form new memories. If he met someone who then left the room, within minutes he had no recollection of the person or their meeting.

What was a tragedy for Molaison led to one of the most significant turning points in 20th century brain science: the understanding that complex functions such as learning and memory are tied to discrete regions of the brain.

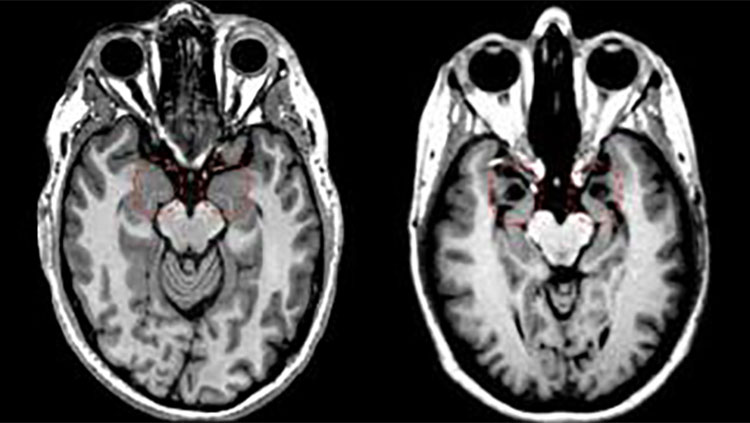

In 1955, scientists William Beecher Scoville and Brenda Milner began studying Molaison — referred to as H.M. to protect his privacy — and nine other patients who had undergone similar surgery. Only patients who had specific portions of their medial temporal lobes removed experienced memory problems. And, the more tissue removed, the more severe the memory impairment. The researchers noted patients’ amnesia was “curiously specific to the domain of recent memory.”

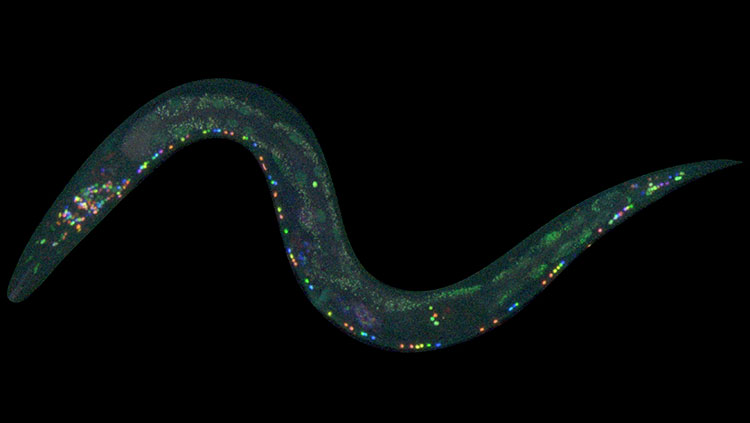

Scoville and Milner’s observations pointed to a particular structure within the medial temporal lobe that was necessary for normal memory — the hippocampus. Over the next five decades, neuroscientists studying Molaison learned that the hippocampus and adjacent regions transform our transient perceptions and awareness into memories that can last a lifetime.

For Molaison, this transformation could no longer take place. He experienced every aspect of his daily life — eating a meal, taking a walk — as a first. Yet his intellect, personality, and perception were intact, and he was able to acquire new motor skills. Over time, he became more proficient at tasks such as tracing patterns while watching his hand movements in a mirror, despite the fact that he could never recall performing the task before.

Studies of Molaison paved the way for further exploration of the brain networks encoding conscious and unconscious memories. Even after his death in 2008 at the age of 82, neuroscientists continue to learn from him.

This article was adapted from the 8th edition of Brain Facts by Deborah Halber.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Scoville, W. B., & Milner, B. (1957). Loss of Recent Memory After Bilateral Hippocampal Lesions. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 20(1), 11–21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC497229/

Squire, L. R. (2009). The Legacy of Patient H.M. for Neuroscience. Neuron, 61(1), 6–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.023