Oil and Brains Don’t Mix

- Published23 Jan 2024

- Author Emily Shepherd

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

Deep in the Earth's crust, thousands of feet below the seafloor, which was thousands of feet below the ocean's surface, an oil reservoir experienced a sudden release of pressure. It was April 20, 2010, and something had gone awry at the Macondo well 50 miles off the coast of Louisiana in the Gulf of Mexico. Oil surged out of the human-made bore. The rupture at the well created a cascade of effects, causing the oil rig floating directly above the well on the ocean’s surface to explode. The oil rig was named Deepwater Horizon, and the ensuing oil spill would bear the rig's name.

The explosion killed 11 people working on the oil rig and injured several others. Before the Macondo well would be capped 87 days later, the reservoir would spew four million barrels of oil and 250 thousand metric tons of gasses into the Gulf of Mexico. It was the largest oil spill in U.S. history, and it required tens of thousands of people to clean up the worst of it.

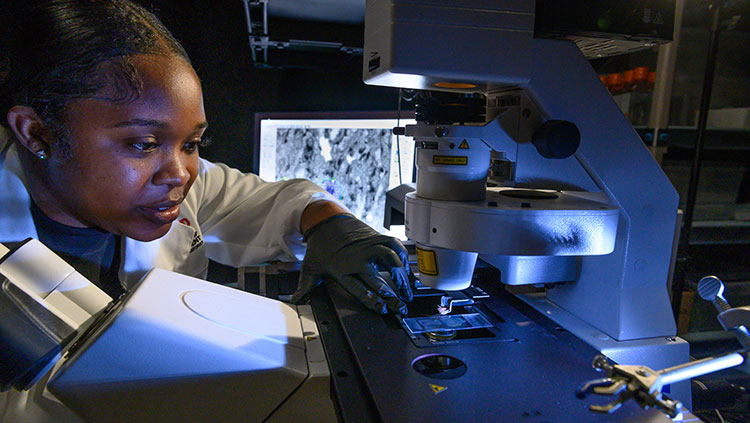

Scientists also responded, creating two of the largest studies ever to document the effects of oil spills on responders: the Gulf Long-term Follow-up Study (GuLFStudy) and the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Coast Guard Cohort Study. The GuLFStudy initially enrolled 24,937 responders who worked at least one day on clean-up. It is the largest study to ever examine the health effects of an oil spill. The Coast Guard Study enrolled 8,696 responders — all members of the U.S. Coast Guard — who were involved for at least one day on the response. The GuLFStudy mostly used health questionnaires and at-home medical exams over time, whereas the Coast Guard Study collected diagnoses that responders received from doctors, revealing the emotional and neurological effects of disaster response exposure to oil and cleanup chemicals.

Oil Gets Everywhere

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill released enormous underwater plumes, somewhat like the plumes of smoke that rise from wildfires. The oil affected “every single stratum of the water column,” said oceanographer Claire Paris-Limouzy with the University of Miami. She worked with a team of researchers to show that the extent of the plume underwater was much bigger than the footprint on the ocean surface. Both oil and chemical dispersants deployed into the deep ocean hurt many kinds of animals, including corals, fishes, and mammals. “You have not only the marine ecosystem,” said Paris-Limouzy, “but also the land base system with birds, mangroves, marshes, estuaries — all this was affected.”

Responders moved into these ecosystems and worked to reduce the impacts of the oil. They deployed berms — long, floating devices meant to absorb or corral the oil — around coasts, skimmed up or burned oil slicks on the water’s surface, and sprayed chemical dispersants meant to disintegrate the oil. Later evidence suggested the dispersant injection at depth was not effective at mitigating the spill since the oil was released from a deep blowout.

During cleanup, responders often inhaled fumes and got the oil on their skin, with neurological consequences. Many experienced conditions like stress, depression, anxiety, migraines, tinnitus, and nerve damage.

Oil Spill Disasters Affect Mental Health

Sarah Lowe, clinical psychologist at the Yale School of Public Health, and her team of researchers with the GuLFStudy followed up with 10,141 study participants and found cleanup work was associated with higher post-traumatic stress, major depression, and generalized anxiety disorder. “Participants who worked longer hours and who had jobs that had more direct contact with oil tended to fare worse in their mental health,” said Lowe, “showing that it wasn’t just being involved in the cleanup, but having these exposures that might be physically strenuous or could expose people to sights, smells, sounds, et cetera, of the impact that were contributing to mental health symptoms.”

But Lowe and her team found one unusual pattern nearly two years after the spill. “Some people who tended to work for more days or who worked in jobs that had a lot of oil exposure, their income that year was higher than their counterparts’. And that actually had a positive effect on mental health.” In the paper publishing these findings, Lowe and her team noted the apparent paradox might be explained by the fact that higher income could “ease general anxiety and hopelessness about the future, but not protect against mental health symptoms directly connected to trauma exposure.”

Must Be Oil on the Brain

A certain class of volatile organic compounds in oil called BTEX (benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylene) is known to affect the neurophysiological health of humans. According to the Toxicology Profile for Benzene published by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2007, there is a cause-and-effect relationship between benzene and toxicity to the nervous system. The chemical is relatively biodegradable in low concentrations. But in high concentrations, like an oil spill, it biodegrades slowly.

Dispersants, a “composition of detergents, solvents, and surfactants,” were also a part of the disaster response, said Jennifer Rusiecki, epidemiologist with Uniformed Services University and lead author of the Coast Guard Cohort Study. No Coast Guard responders deployed dispersants. However, the dispersant “could make the oil more toxic,” to anybody exposed, she said.

Most research into the neurotoxicity of BTEX concerns exposures exceeding recommended thresholds indoors, like working in a factory near the chemicals for years. The GuLFStudy and the Coast Guard Cohort Study were able to investigate neurological health impacts for people who experience weaker exposures, like working outside near the chemicals for a few months.

Two GuLFStudy papers, one investigating single maximum exposures and the other investigating cumulative exposures, examined just how much BTEX exposure can affect neurological function. The first paper found there was not an impact from the exposure on cognitive functions on the majority of tests — but there was some indication that higher-exposure jobs were associated with slower neurobehavioral response times. The second paper found there was not a significant relationship between spill-related chemical exposure and neurological function on many tests. However, in responders older than 50 years, greater cumulative exposure to BTEX resulted in modest reductions to somatosensory and motor system function several years after the spill.

In both studies, the highest observed exposures were still below standard regulatory limits set by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (benzene, 1000 ppb; toluene, 200,000 ppb; ethylbenzene, 100,000 ppb; xylene, 100,000 ppb). The authors of the latter study conclude it’s possible their measurements recorded “subtle, subclinical effects that may occur earlier in disease progression” — hinting that toxicity may occur from lower levels of BTEX exposure.

The Coast Guard Cohort Study investigated medical records of Coast Guard responders, evaluating risk for neurological health problems after oil exposure. Unlike the studies mentioned above, this study did not just investigate subtle signals indicating reduced neurological function. Rather, the Coast Guard Study investigated the medical records of people who had “enough of these problems to seek medical attention,” said Rusiecki, up to five years after the spill. The main neurological conditions her team found associated with oil spill response work were headaches and migraines, tinnitus (ringing in the ear), and mononeuritis (a condition involving damage to the nerves).

Mind Over Oil

While the exact processes that start at oil exposure and end with the development of neurological conditions are not perfectly understood, Rusiecki said scientists have well-developed theories. “These diseases from exposure to the chemicals that we’re talking about are typically through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and possibly epigenetic mechanisms,” said Rusiecki.

“Oxidative stress is the imbalance between the production of oxidants and antioxidants that can result in an accumulation of reactive oxygen species, and that results in damage to cells because it damages their lipids, proteins, and DNA,” she said. Additionally, BTEX and other ultrafine particulate matter from oil can cross the blood-brain barrier, affecting the central nervous system directly.

In the future, both Lowe and Rusiecki say that, along with preventing oil spills altogether, reducing the workloads of individual responders can reduce their chances for health problems. “It’s important for the leadership involved in disaster response to have an appreciation of the health risks that their people are going to be exposed to when they respond to a disaster like an oil spill,” said Rusiecki.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

References

Berenshtein, I., Paris, C. B., Perlin, N., Alloy, M. M., Joye, S. B., & Murawski, S. (2020). Invisible oil beyond the Deepwater Horizon satellite footprint. Science Advances, 6(7), eaaw8863. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw8863

Chen, D., Werder, E. J., Stewart, P. A., Stenzel, M. R., Gerr, F. E., Lawrence, K. G., Groth, C. P., Huynh, T. B., Ramachandran, G., Banerjee, S., Jackson Ii, W. B., Christenbury, K., Kwok, R. K., Sandler, D. P., & Engel, L. S. (2023). Exposure to volatile hydrocarbons and neurologic function among oil spill workers up to 6 years after the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Environmental Research, 231, 116069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.116069

Eargle, L. A., & Esmail, A. (Eds.). (2012). Black Beaches and Bayous: The BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Disaster. University Press of America, Incorporated.

Kwok, R. K., Engel, L. S., Miller, A. K., Blair, A., Curry, M. D., Jackson, W. B., Stewart, P. A., Stenzel, M. R., Birnbaum, L. S., Sandler, D. P., & GuLF STUDY Research Team (2017). The GuLF STUDY: A Prospective Study of Persons Involved in the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Response and Clean-Up. Environmental Health Perspectives, 125(4), 570–578. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP715

Lowe, S. R., Kwok, R. K., Payne, J., Engel, L. S., Galea, S., & Sandler, D. P. (2016). Why Does Disaster Recovery Work Influence Mental Health? Pathways through Physical Health and Household Income. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58(3–4), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12091

National Commission on the BP Deepwater. (Ed.). (2011). Deep Water: The Gulf Oil Disaster and the Future of Offshore Drilling: Report to the President, January 2011: The Gulf Oil Disaster and the Future of Offshore Drilling. United States Government Printing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GPO-OILCOMMISSION

Paris, C. B., Berenshtein, I., Trillo, M. L., Faillettaz, R., Olascoaga, M. J., Aman, Z. M., Schlüter, M., Joye, S. B. (2018). BP Gulf Science Data Reveals Ineffectual Subsea Dispersant Injection for the Macondo Blowout. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5(389). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00389

Quist, A. J. L., Rohlman, D. S., Kwok, R. K., Stewart, P. A., Stenzel, M. R., Blair, A., Miller, A. K., Curry, M. D., Sandler, D. P., & Engel, L. S. (2019). Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Exposures and Neurobehavioral Function in GuLF Study Participants. Environmental Research, 179, 108834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2019.108834

Rusiecki, J., Alexander, M., Schwartz, E. G., Wang, L., Weems, L., Barrett, J., Christenbury, K., Johndrow, D., Funk, R. H., & Engel, L. S. (2018). The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill Coast Guard Cohort study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 75(3), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2017-104343

Toxicological Profile for Benzene. (2007). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/ToxProfiles/ToxProfiles.aspx?id=40&tid=14