Colliding Senses: Life With Synesthesia

- Published27 Dec 2018

- Reviewed27 Dec 2018

- Author Jessica P. Johnson

- Source BrainFacts/SfN

What color is the letter A? Is the number 7 a confident woman or a shy little boy? What does your favorite song taste like? If you’re like 95 percent of the population, these questions probably don't make any sense.

People with synesthesia, or synesthetes, however, experience a tangling of two or more senses when they encounter specific stimuli. These stimuli provoke involuntary sensations of touch, taste, vision, sound, smell, or even emotion that they don’t trigger in most people.

Listen as neuroscientists Julia Simner and Edward Hubbard describe the brain of a synesthete and the possible benefits of having this ability.

CONTENT PROVIDED BY

BrainFacts/SfN

Transcript

BrainFacts.org: I’m Jessica Johnson for BrainFacts.org.

What color is the letter A? Is the number 7 a confident woman or a shy little boy? What does your favorite song taste like?

If you’re like 95 percent of the population, these questions probably don’t make any sense. But for people with synesthesia, the idea that a written word can evoke visions of color, or that inanimate letters and numbers have gender and personality, or that sounds have different flavors is as natural as having a nose on your face.

People with synesthesia, or synesthetes, experience a tangling of two or more senses when they encounter specific stimuli. These stimuli provoke involuntary sensations of touch, taste, vision, sound, smell, or even emotion that they don’t trigger in most people. The sensory mismatches can happen in any number of combinations—and at least 128 types of synesthesia have been documented so far. I spoke with a pair of scientists who have been collaborating on synesthesia research for almost a decade.

Julia Simner: I'm Julia Simner. I'm a professor of psychology, neuropsychology, and neuroscience at the University of Sussex in the UK and I run the Multisense Synaesthesia Research Lab looking at synesthesia across the lifespan.

I've got two favorites. One of them is having personalities for letters and numbers. The other is having tasty words. So, we call this lexical-gustatory synesthesia. It's triggered by listening to words, speaking words, and even thinking about words. And the experience that derives from that is a flooding of flavor in the mouth. It has quite complex linguistics determining which words will trigger which flavors.

BF: The different types of synesthesia are often named for the stimulus that triggers a sensation, followed by the sense that is stimulated. For example, auditory-tactile synesthesia is hearing a specific sound and feeling a physical sensation in a specific part of your body. And grapheme-color synesthesia is seeing letters or numbers (collectively called graphemes) in colors that aren’t visible to others.

Edward Hubbard: The classic sort of way that we talk about this is a merging of the senses.

I am Edward Hubbard. I’m an assistant professor in educational psychology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison where we investigate numerical cognition, multi-sensory integration, synesthesia, and the impact of these sorts of things on children's brain development especially in educational settings.

One of my favorites really is this number-form synesthesia. This map between numbers, but also days of the week, months of the year, and spatial locations around the body.

BF: The number-form type of synesthesia was the most difficult for me to understand. The way I picture it is that people visualize series of numbers floating in space in a precise arrangement, similar to how you might organize necessary items on a desk or around your apartment. So that they’re within easy reach when you need them and carry extra meaning based on the way they’re arranged.

EH: I think that, in general, synesthetic associations are shaped by our complex lifetime of experiences. In Western societies when we write from left to right, we associate small numbers with the left side of space and large numbers with the right side of space. But most of us do so unconsciously. For synesthetes, they have this full-blown rich experience. So, when we look at what happens in synesthesia, we see, in a more explicit or flagrant form, the same sorts of processes that are happening in all of us.

BF: So, understanding the exaggerated and melded perceptions of people with synesthesia might one day help us understand processing in more typical brains. Recent advances in brain imaging techniques have reinvigorated research on the synesthetic brain. Before these tools were available, many people were not convinced that synesthesia even existed.

EH: Many people would intuitively be skeptical because they don't share that experience and it's hard to verify. The brain imaging studies that showed consistent differences in structure and function in synesthetic brains versus non-synesthetic brains, I think, went a long way towards convincing some of the holdouts that this was a real phenomenon worthy of study.

BF: You can imagine that growing up with synesthesia might make you think that everyone experiences the world the way you do. But that’s hardly the case.

EH: Only approximately 5% of the population experience these types of associations.

BF: Some people with synesthesia describe the experience as having a super power that helps them produce art or navigate encounters with strangers, such as in the case of synesthetes who see people emitting colors that change the more they get to know them. But others may describe the experience as neutral, an uncomfortable distraction, or having a negative impact on their daily lives.

JS: When you talk to synesthetes you'll get a range different answers when you ask them, How is it to have synesthesia? Overall, synesthesia can be a positive thing, but it's not always a positive thing.

I'm contacted quite often by clinicians who are working with children with autism, for example, who also have synesthesia. And that combination seems to be particularly difficult. We have children who are aversive to certain letters because they don't like their synesthetic associations and have sensory sensitivities that are affecting their daily life.

BF: The UK’s National Health Service has recently added synesthesia to its list of “read codes,” which are codes that doctors use to report and track patients’ conditions. This can provide relief, Simner says,

JS: For the small number of people that are experiencing difficulties from it or just for those who want to be reassured that it's completely fine and normal in many ways.

EH: Synesthesia is not a disease.

BF: There are even some suggestions that it might be beneficial.

JS: We've screened around five to six thousand children individually for synesthesia and we've given them a battery of tests. And so far, across the board in academic subjects, the synesthetes are significantly better than their controls at numerical cognition, language literacy, and all those kinds of cognitive tasks that we've looked at so far.

ES: I was going to elaborate on that a little bit. All the way back to the late sixties, there has been this consistent finding that synesthetes can have enhanced memory. So, we're thinking about how synesthesia might reflect a more general propensity for us to use multiple senses and multiple pieces of information in trying to remember something. But the synesthetes essentially get this for free because every time they experience a number they also get the color, and they have an additional advantage because they've learned over a lifetime of experience that this color goes with this number and this number goes with those colors. So, they can use each cue symmetrically to retrieve the other bit of information.

JS: I think it's also important to point out that it's not all good news for synesthetes. We recently ran a very large screening study of several thousand adults. We found that synesthetes are significantly more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety disorder.

BF: Simner cautions that such association studies are still in their nascent stages and causative relationships have yet to be established. But the results will hopefully encourage additional research that will help us better understand the brain.

There are lots of competing theories about how the brains of people with synesthesia produce such unusual blending of the senses and why the sensory combinations can manifest so differently in individuals, but none have yet produced definitive answers. Hubbard described one theory using the example of grapheme-color synesthesia.

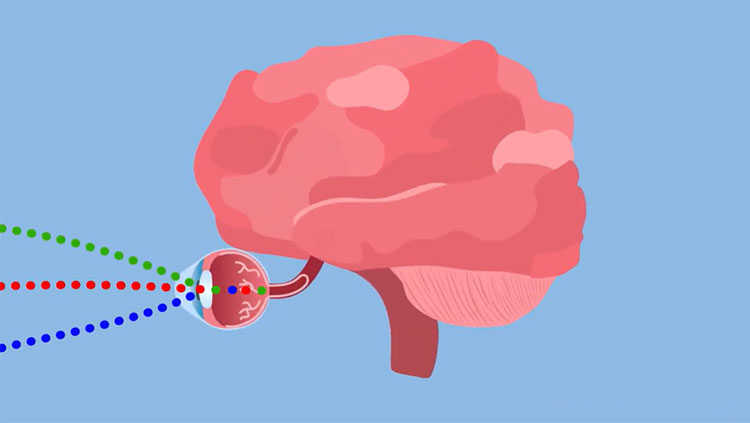

EH: One model is this idea of what we call the hyper-connectivity model. We know that there are brain regions that are involved in visual word recognition and they lie adjacent to brain areas that are involved in color processing. And it's been known since the 1880s that synesthesia runs in families. And so, if we think that there is some genetic factor that causes either excessive connectivity or reduction in the typical pruning process, these brain areas would remain connected such that whenever somebody sees a letter or a number, they would then also cross-activate these color selective areas and that would lead to the experience of seeing colors in addition to seeing the letters or numbers.

BF: Hubbard says MRI scans of synesthetes’ brains often reveal two key differences: thicker gray matter, which is the brain tissue containing neuron cell bodies, and greater connectivity or wiring between widespread regions of the brain.

Despite the atypical features and functionality revealed in brain scans, Hubbard reminds us that we shouldn’t view the brain activity of people with synesthesia as abnormal. They simply represent one end of a spectrum where sensory inputs can trigger stronger and more widespread brain activity than in people without synesthesia.

EH: It is a variant in our normal everyday perception that a significant minority of the population experience.

BF: In addition to brain imaging studies and psychological screening, scientists have also begun to search for genes that might predispose individuals to developing synesthesia by looking for gene variants in families with a higher than average number of synesthetes. So far, these studies have uncovered some basic patterns.

EH: A large number of genes were ones that were all involved in basic neurodevelopmental processes like axon guidance, axon wayfinding, potentially some aspects of synapse stabilization and pruning.

BF: Synesthesia is also more common in children than in adults, especially children who grew up bilingual. This suggests that synesthesia may arise or subsequently disappear during the process of normal brain development. And contrary to recent theories, women are not more likely to have synesthesia than men.

JS: I've gone out into the population and individually screened seventeen and a half thousand people for synesthesia at this point, and in every study I've done, at every age I've done, I have never once found a significant difference between men and women or boys and girls. So, I'm fairly confident to say that the earlier finding of more women was a reporting bias.

BF: So far, there are no documented cases of synesthesia naturally appearing after people reach adulthood.

JS: When synesthesia does spontaneously arise in an adult, it tends to be the result of trauma or disease or something that would allow us to label that as an acquired synesthesia rather than the kind of developmental synesthesias we’ve been talking about.

BF: Such was the case of a man who became blind from a brain injury but began seeing colors whenever he heard people speak the names of numbers. Or a man with retinitis pigmentosa who, after going blind, noticed a red cartoon-like face begin to appear in his visual field, which then gained detail and 3-D depth over time. He also saw flashing, swirling, or jumping visions of objects he touched with his hands.

Acquired synesthesia is very rare. But as scientists reach out to the public more and more, they’re finding that developmental synesthesia is a lot more common than once thought.

JS: So, the question of how common synesthesia is, is something that's been around in the literature for the last couple hundred years. The prevalence of synesthesia is probably at least 4 percent. That's from a study we ran in 2005 where we screened for around 128 different types of synesthesia. It might feel quite rare, but when you scale that up to the population of the planet, that's equivalent to the entire population of the United States. There are many important variants of synesthesia that we didn't test for. We did not include personality synesthesia, spatial synesthesia, mirror-touch synesthesia. So, I would suggest that the prevalence of synesthesia is somewhat higher than that.

BF: So much still remains to be learned about synesthesia. One question in particular is, from an evolutionary standpoint, why is synesthesia so common relative to other rare genetic variants and why has it stuck around in the population?

EH: One possibility is it does confer an advantage and we haven't been able to identify that advantage. My general take on this is that it's also quite likely that it's sort of evolutionarily neutral. If it wasn't selected against, it would be here present in the population as a consequence of all of the other genetic variability that gives rise to the brain systems that we have.

JS: Yes, so something a bit like earlobe size. It's a variation in the population that’s not going to be screened out anytime soon, so it continues. A lot of the debate today has been centered around the question of whether synesthetes are qualitatively different to the average person or whether they exist on a continuum with the average person, and I think we've decided that, either way, understanding synesthetes’ brains is a fundamental tool, if you like, to understand the average brain.

BF: Thanks for listening. Check out more information about synesthesia’s many forms at BrainFacts.org.